Rascals case in brief

In the beginning, in 1989, more than 90 children at the Little Rascals Day Care Center in Edenton, North Carolina, accused a total of 20 adults with 429 instances of sexual abuse over a three-year period. It may have all begun with one parent’s complaint about punishment given her child.

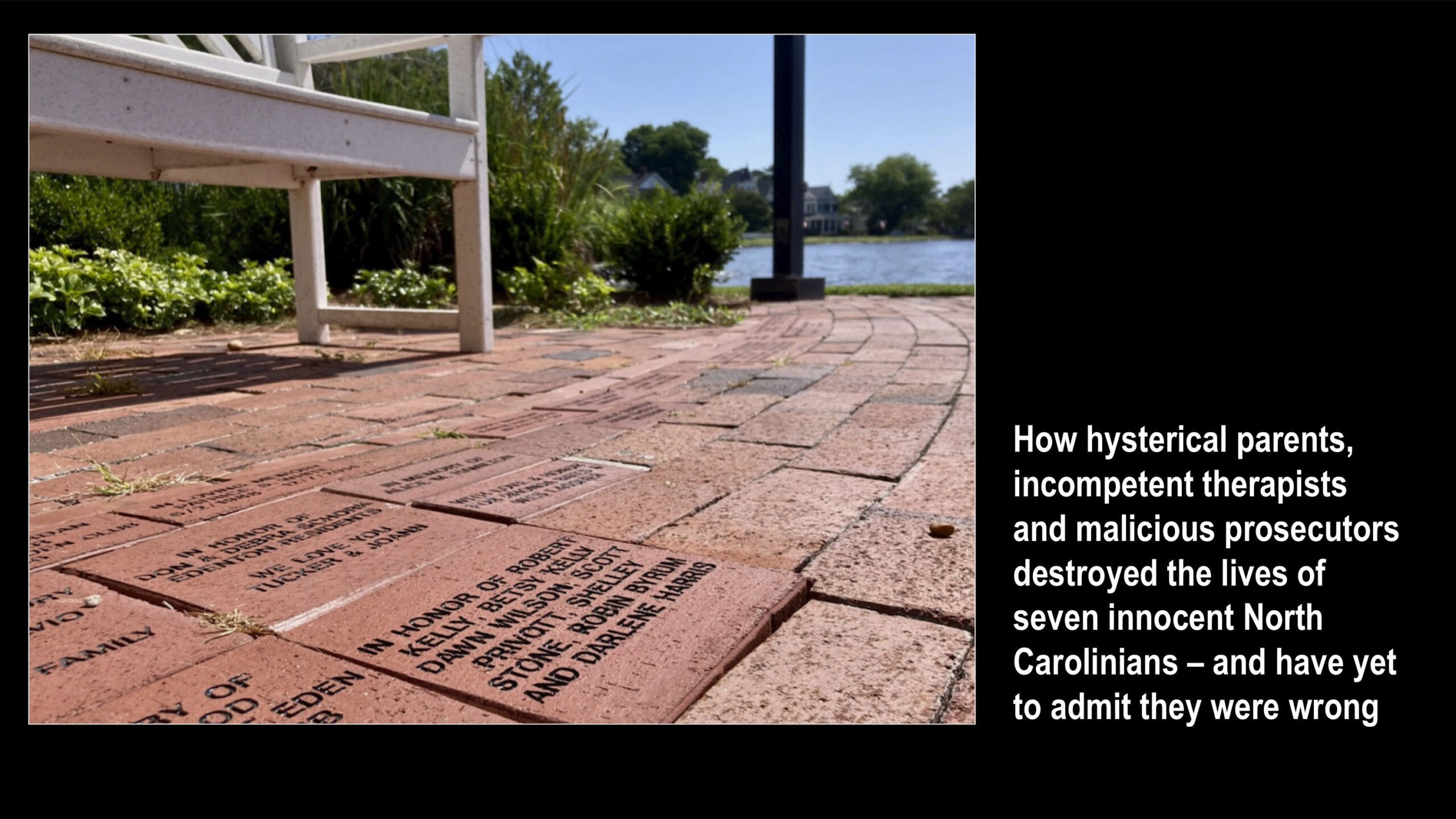

Among the alleged perpetrators: the sheriff and mayor. But prosecutors would charge only Robin Byrum, Darlene Harris, Elizabeth “Betsy” Kelly, Robert “Bob” Kelly, Willard Scott Privott, Shelley Stone and Dawn Wilson – the Edenton 7.

Along with sodomy and beatings, allegations included a baby killed with a handgun, a child being hung upside down from a tree and being set on fire and countless other fantastic incidents involving spaceships, hot air balloons, pirate ships and trained sharks.

By the time prosecutors dropped the last charges in 1997, Little Rascals had become North Carolina’s longest and most costly criminal trial. Prosecutors kept defendants jailed in hopes at least one would turn against their supposed co-conspirators. Remarkably, none did. Another shameful record: Five defendants had to wait longer to face their accusers in court than anyone else in North Carolina history.

Between 1991 and 1997, Ofra Bikel produced three extraordinary episodes on the Little Rascals case for the PBS series “Frontline.” Although “Innocence Lost” did not deter prosecutors, it exposed their tactics and fostered nationwide skepticism and dismay.

With each passing year, the absurdity of the Little Rascals charges has become more obvious. But no admission of error has ever come from prosecutors, police, interviewers or parents. This site is devoted to the issues raised by this case.

On Facebook

Click for earlier Facebook posts archived on this site

Click to go to

Today’s random selection from the Little Rascals Day Care archives….

Click for earlier Facebook posts archived on this site

Click to go to

Today’s random selection from the Little Rascals Day Care archives….

Prosecutors learned wrong lesson from McMartin

March 28, 2012

Had North Carolina prosecutors been interested in anything other than racking up convictions, they would’ve given earnest consideration to analyses such as this one in the Los Angeles Times in 1990, barely a week after a jury returned not guilty verdicts in the McMartin Pre-School case:

“Experts across the country say the interview techniques intended to extract the truth from youngsters who attended the Manhattan Beach nursery school were so misguided as to make the children seem coerced, rehearsed and ultimately unbelievable to the jury….

“According to both child development and criminal defense experts who have closely monitored the case for the last six years, some of the adults — the parents, the prosecutors, the therapists — who tried hardest to find out what happened in the first place may have done the most to confuse the case in the end…. Most of the children were never given the chance to simply tell what, if anything, happened to them.

“‘They were never given the opportunity to tell their stories as they knew them, in their own words, until long after their minds had been contaminated with the thoughts and fears of the adults around them,’ said David Raskin, a psychologist at the University of Utah who has been studying child abuse cases for the last 15 years. By then, he said, it was too late.”

Contamination proved every bit as rampant among child-witnesses in the Little Rascals case, but prosecutors had learned from McMartin to conceal it by denying access to verbatim records of therapists’ interviews.

What caused ‘inability to think straight’?

Aug. 29, 2012

“Los Angeles County’s Satanic Abuse Task Force, an official sub body of the Los Angeles County Women’s Commission, concluded (in 1992) that Satanists were trying to pump diazinon poison into their office and home air vents in order to silence them. Task force members became suspicious, according to president Myra Rydell, after experiencing bouts of profound exhaustion, headaches and, perhaps most significantly, ‘the inability to think straight.’

“McMartin parent Jackie McGauley, also a task force member, told a reporter that, according to her doctor, diazinon would be ‘virtually impossible to detect’ if given in small doses over a long time period. The County’s epidemic specialist said that diazinon was easy to detect and after his own investigation called the claims ‘outrageous.’”

– From “The Dark Truth About the ‘Dark Tunnels of McMartin’” by John Earl (IPT Journal, 1995)

No single reason accounts for the country’s belated skepticism about ritual abuse, but the poison-gas episode in Los Angeles surely qualified as a “jump the shark” moment.

The limits of ‘unequivocal and undeniable evidence’

April 1, 2013

April 1, 2013

“Suppose an individual believes something with his whole heart; suppose further that he has a commitment to this belief, that he has taken irrevocable actions because of it; finally, suppose that he is presented with evidence, unequivocal and undeniable evidence, that his belief is wrong; what will happen?

“The individual will frequently emerge, not only unshaken, but even more convinced of the truth of his beliefs than ever before….”

– From “When Prophecy Fails” by Leon Festinger, Henry Riecken and Stanley Schachter (1956)

The three social psychologists studied the refusal of a cult of UFO believers to accept that their belief in an imminent apocalypse had been proven false. Seth Mnookin usefully dusts off this case in “The Panic Virus: A True Story of Medicine, Science and Fear,” his 2011 expose of the groundless claim that childhood vaccination causes autism.

Before the day-care ritual-abuse mania ran its course, its theorists and trophy hunters clung ever more tightly to a belief system with no rational means of support. Long after the phoniness of the Little Rascals prosecution had become clear to the world, Nancy Lamb managed to conjure up an unrelated abuse charge against Bob Kelly. And even today…

McMartin interviewers showed way for Little Rascals

April 25, 2012

“Many questions were repeated (by interviewers in the McMartin Preschool case) even when the children had previously given unambiguous answers.

“For example, after a child responded that he/she did not remember any pictures of naked bodies, the interviewer repeated the question saying, ‘Can’t remember that part?’

“Even after the child again responded ‘no,’ the interviewer persisted, saying ‘Why don’t you think about that for awhile…. Your memory might come back to you.’ ”

– From “Tell Me What Happened: Structured Investigative Interviews

of Child Victims and Witnesses” by Michael E. Lamb, et al. (2008)

There is every reason to believe this approach typified interviews in the Little Rascals case, but of course prosecutors ensured almost no record of those interviews survived.

0 CommentsComment on Facebook